The Banality of Evil & You

What you can do about ICE, the banality of evil, and political information

I recently posted a 4-part series of videos on the Necessary Evil instagram account talking about recent developments in ICE enforcement and what you, as an engaged person who wants to do the hard work of creating political change, can do about it all.

There are so many entry points for thinking about problems like this, but for me it's grounding and organizing to situate our current reality in history, and also in theory. That's not to say that you need to read a lot of academic literature to understand what's going on—it IS to say that, so many of the issues we confront today have been confronted before, they're older than us and have legacies of dominance and resistance that we can plug into and learn from, if we know where to look. So my goal with this series is to take you through one of those pathways, thinking about Hannah Arendt and the "banality of evil."

Contending with ICE abductions in 2025 is something you can do with the aid of technology, but it starts with knowing what’s happening, what you’re looking at, and that you have to intervene.

What's happening with ICE and why are we talking about the 1940s?

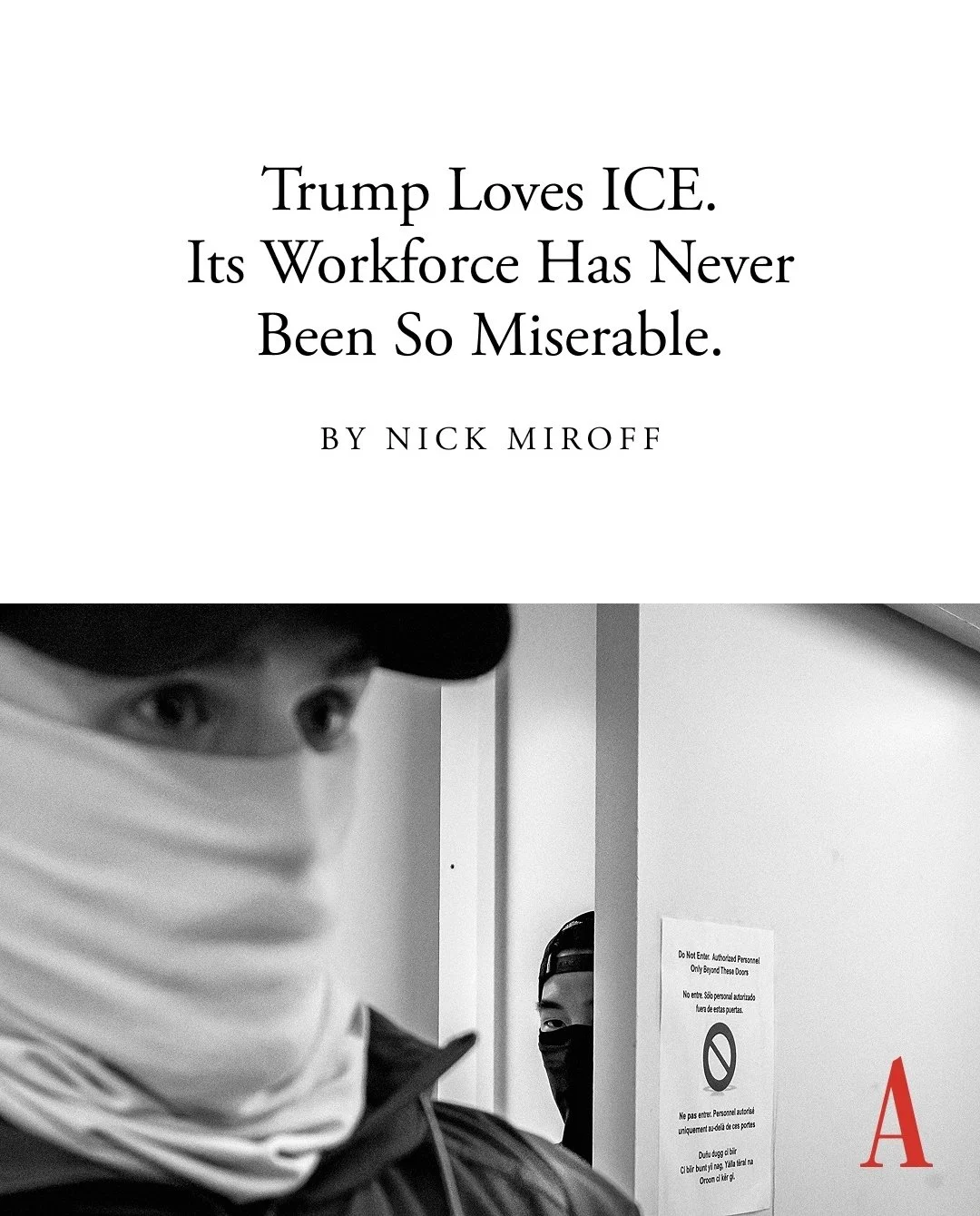

If you're not familiar or aware of what's happening, there are a few good overviews you can read already, but the upshot is this: even though the groundwork for deplorable conditions for migrants, no matter their documentation status, was laid decades ago under even Democratic administrations, the Trump regime has accelerated efforts to dragnet immigrants, abduct people from their homes, schools, and workplaces, and deport them or detain them to unknown fates. I don't use words like "abduct" ironically, metaphorically, or hyperbolically. Video footage shows masked agents with no official insignia descending on people in unmarked vehicles, breaking car windows and doors, and battering into private residences to take people, often without a warrant or any pretext of legal mandate.

Some very reasonable people will react to footage like this with horror, dismay, discomfort...and then quick attempts to rationalize. "Well there must be a reason," "people who haven't done anything wrong don't have anything to fear," "people who have papers, hardworking people, those aren't the ones they're after." On the other end of the spectrum, many have drawn hasty comparisons to the early years of the Nazi regime, perhaps not realizing how much the Third Reich adapted strategies used in the United States in the decades prior. Or that there have been so many examples of oppression, state-sponsored violence, and fascism that existed beyond Germany.

The analysis I want to offer you isn't trying to leverage yet another one of those facile comparisons to the German regime. What I do want to do, though, is to point to that moment in history, and in theory, because we learned so much about how to think about moral calculus under unjust laws and oppressive regimes in that moment. So much thinking and writing about exactly these problems emerged in the wake of the Holocaust, and we would be remiss not to offer ourselves some of that thinking in this moment as an antidote to paralysis.

What does this have to do with me ?

You can watch each short video to get more details, but one of the reasons I started Part 1 with the article detailing the motivations of people seeking employment with ICE/CBP/DHS was to illustrate how mundane and normal the kinds of forces are that drive us to consider implicating ourselves in oppressive and violating activities. They're the same kinds of motivations and obligations that prevent us from taking positive action too: we have a mortgage or rent to pay, we have kids to put through school, we have to be able to afford groceries, and ultimately what we want is to be able to live a Good™ life, one we can afford and that offers enjoyment and fulfillment.

Perhaps people being interviewed for a news story weren't entirely honest about their motivations—maybe they felt at least some social pressure not to appear xenophobic or racist, although a few certainly weren't constrained by those expectations—so all we're left with is the more typical desires to make a living wage and get to see the world. But I would argue that most people actually don't have strongly held convictions and firm beliefs that lead them to racist ideologies or behaviors. What they have instead are a lot of unexamined beliefs and inherited ideas, either sucked up through osmosis in social environments imbued with latent racism and stereotyping, or slowly and incrementally inculcated through years of education that simply omitted key pieces of information or perspectives. Those kinds of people are the ones I want to talk about.

Why? Because they're your neighbors. I don’t mean that in the abstract sense; I mean it very concretely. These are the people attending your gym, taking your classes, carpooling with you on weekend trips, attending your potlucks, making the comments you cringe to overhear. They are the ones most accessible and susceptible to the kinds of social pressure you can impart against participating in horrific acts of oppression and violence, and they are also the kinds of people you can reach and help to provide the life they're looking for and that we all want: the kind of life where they are able to afford basic necessities and experience some amount of accomplishment, fulfillment, relaxation—maybe even joy.

Looking back helps us plan ahead

Part 2 and Part 3 of the explainer series are mostly focusing on historical and theoretical interventions made decades ago, but ones that are important to understand today as you situate yourself in the current political moment. In part 2, I spent time talking through Hannah Arendt's observations of Adolf Eichmann, the famous architect of the Nazi's "Final Solution," that she detailed as a series of articles that were then collected in Eichmann in Jerusalem. Observing his over-reliance on flowery language and bureaucratic jargon, and his emphasis on his career ambitions, Arendt concluded at the time that Eichmann represented what she called the "banality of evil"—not someone who was motivated by malice or ill-intent, but rather something much more normal, a desire to get ahead personally in ways that lend themselves to unthinking behavior at others' expense. If you read the article interviewing prospective new ICE agents, you could be forgiven for seeing a resemblance there: people not so much thinking about the very real human consequences of their participation in an oppressive bureaucracy, but mainly focused on having a job where they can apply their skills and make an impact.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

There are many, many valid critiques of Arendt's characterization of Eichmann—including very detailed biographies that demonstrate his overt commitment to anti-Semitic ideologies, and ways that he reveled in his notoriety for such brutal work—but her concept has significant durability across space and time. Certainly it doesn't help us explain the root of evil in the world at all, but it does offer one possibility for understanding how so many people are sucked into the dragnet of using their labor and their bodies to support fascist regimes.

If it's true that evil can emerge from that type of banality, then resisting that slide in the realm of banality should be possible too. Elizabeth Minnich's (newly updated) take on this, the "evil of banality," turns the concept on its head to suggest that it is exactly when we are relieved of the responsibility for thinking, or encouraged not to, that we can be led into evils of this type and scale.

How you've been primed to participate in banal evils

I think many people aren't aware of all the ways they've been encouraged not to think deeply about the underpinnings of the current regime, in part because they're building on foundations laid decades or even centuries ago. It's why I spent most of Part 3 talking about Foucault (if you're new here, I'm sorry; if you've ever met me before, you should've known this was coming), and the transformation of our "modernized" systems of criminality and punishment.

In Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault traces the evolution of our conception and practice of punishment, and how we internalize the state's dictates for behavior in our bodies without even realizing it. Moving away from public execution toward systematized and bureaucratized "justice" systems with prisons absconded from public view was one way, in Foucault's framing, that the state avoided the danger of the public over-identifying with victims of state execution and torture, and essentially manufactured our consent and participation in systems that, at their core, facilitate state-sponsored violence. That practical shift created the ability not only for people to rhetorically shift themselves as being separate from "criminal" elements in society, but also for people to internalize the very state power that would be outwardly wielded on others—to police and subjectify ourselves so that the state didn't have to lift a finger.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

As I describe in the video, I bring up Foucault and this history of criminalization and punishment for two main reasons. The fist is, the rationalization and sanitization of state-sponsored violence in legal punishments and prison systems is part and parcel of what facilitated atrocities like those committed in the Holocaust. The language used to justify corporal punishment by the state mirrors the words used by Eichmann, claiming his actions were needed to protect society, the state, and the nation. Using language of "criminality" justifies subjecting people to punishment and harm at the hands of the state, and here in the so-called United States, we've been brought up in the expectation that our criminal punishment system brings "justice," and that criminals are "deserving" of imprisonment or punishment in ways that prime us all to accept roles in that same system.

I say that by way of explaining that the groundwork for what we're witnessing now with ICE abductions wasn't laid in WW2, but rather long before that, in the formation of modern nation-states. We've all been boiled in a soup priming us to be the exact kind of "yes men" that participate in and embody "banal evils." In short, you've been told what to think about crime and punishment, and then told not to think about it any further. It's easiest to go along with things without thinking.

The second reason I bring this up is to point out that part of what facilitated the sanitization of prisons and punishment was their removal from the public eye—the fact that people were able to distance themselves from "criminals" by removing them from society interrupts the empathy that you would feel with someone suffering as a result of state-based violence. You're encouraged to imagine yourself as someone who fundamentally differs from the kinds of people the state punishes. What feels shocking now, to some, or encourages people to immediately rationalize the violence they see ICE agents committing, is in part that we aren't used to being confronted with the violence that the state subjects certain people to. It's difficult to square that with our unthinking assumption that the process of "law and order" is very systematic, bureaucratic, and "civilized"—whatever that means.

So how does that connect with our ability to participate in atrocities or state-led, bureaucratized violence? The urge to look away, go about your business, not say anything about what's happening in case it makes someone uncomfortable—all of those are impulses that have been systematically but quietly imbued in years of formal education and informal socialization. It's not just that "unthinking" impulses lead hapless people into banal evils in fascist regimes, but rather that all modern states and regimes foster the types of behaviors and beliefs that allow people to become subject to those banal evils.

What should we do?

There's a question I pose in the video series that I think is more important than the simple factual question of whether evil can truly be banal: if evil can be banal, who or what allows it to be that way? Part 4 brings us back to the present day to address that question more concretely.

I alluded to this above, but one of the reasons that the first line of defense and intervention is to pay attention and not look away is exactly because of the information environment we have been raised in—an information environment that removed our ability to witness and empathize with the suffering caused by prisons and our criminal system, that would have allowed us to question who was being subjected to state violence and why. Without having that sense of knowing or the lived experience of education in that reality, we have to work harder to undo our own assumptions about what agents of the state (like ICE) are doing to our neighbors and people in our communities.

You can interrupt the “banality” of evil

Not just for community and your neighbors, but yourself, too. You can make it costly to unthinkingly participate in violence and repression, and you can support all of the desires people have — a living wage, a fulfilling career and life, enjoyment and enlightening experiences — in order to interrupt impulses toward fascism.

If we're connecting to that reality and internalizing that information, our next step is to leverage that knowledge to interrupt others' unthinking participation in the same systems. We can do that through our relationships—family, friends, coworkers—where others know us and trust us enough to hear out how we're feeling, and what we're experiencing. This can look as straightforward as preparing yourself to contend with a family member or a coworker when they say things like "well, they're just rounding up the criminals." Preparing yourself NOT to respond by saying "they're taking more than just criminals" or "these people are hardworking" and ceding the territory that brutalizing and abducting people is ok under any circumstance. But instead, being ready to ground yourself and get brutally honest—that you see the atrocities being committed, that you empathize with people being brutalized, and that you want others to see it too.

Interrupting the "banality" of it all isn't going to topple governments or prevent all harms, as people who have been following the situation in Gaza know all too well. But it's a critical part, and one that you can directly influence, with practice.

--

If that's something you could use support with, I'd encourage you to reach out for 1:1 political peer mentorship—to learn how to analyze and critically engage with what's happening, how to have those hard conversations, and how to stay engaged.

If you'd like a link roundup from this series, and to get future linkdumps and resources, make sure to sign up for the newsletter.